Teachers, in government school, rely on the government to pay their salaries. When there is a teacher shortage at a school, they have to wait for the local authority to allocate them the relevant teacher; if or when governmental funds become available. “Volunteer teachers” are a common feature in schools. These are teachers whose salaries are paid by the monetary contributions of parents from the school community. Often this is the only way that teachers can be secured for such specialty subjects such as the sciences and mathematics. This is why Dylan Parkin’s volunteering at the Nyamatongo Secondary Schools, for free, means so much - because for the first time this year [2020], the secondary students are being taught biology on a regular basis. Dylan’s interactive approach contrasts starkly with the lecture style of teaching and rote learning that is prevalent in most of the other classrooms. Cedar Tanzania is proud to partner with Nyamatongo Secondary School in this way. Here Dylan tells us more about his experience of teaching in a Tanzanian school.

What motivated you to get involved at the local school?

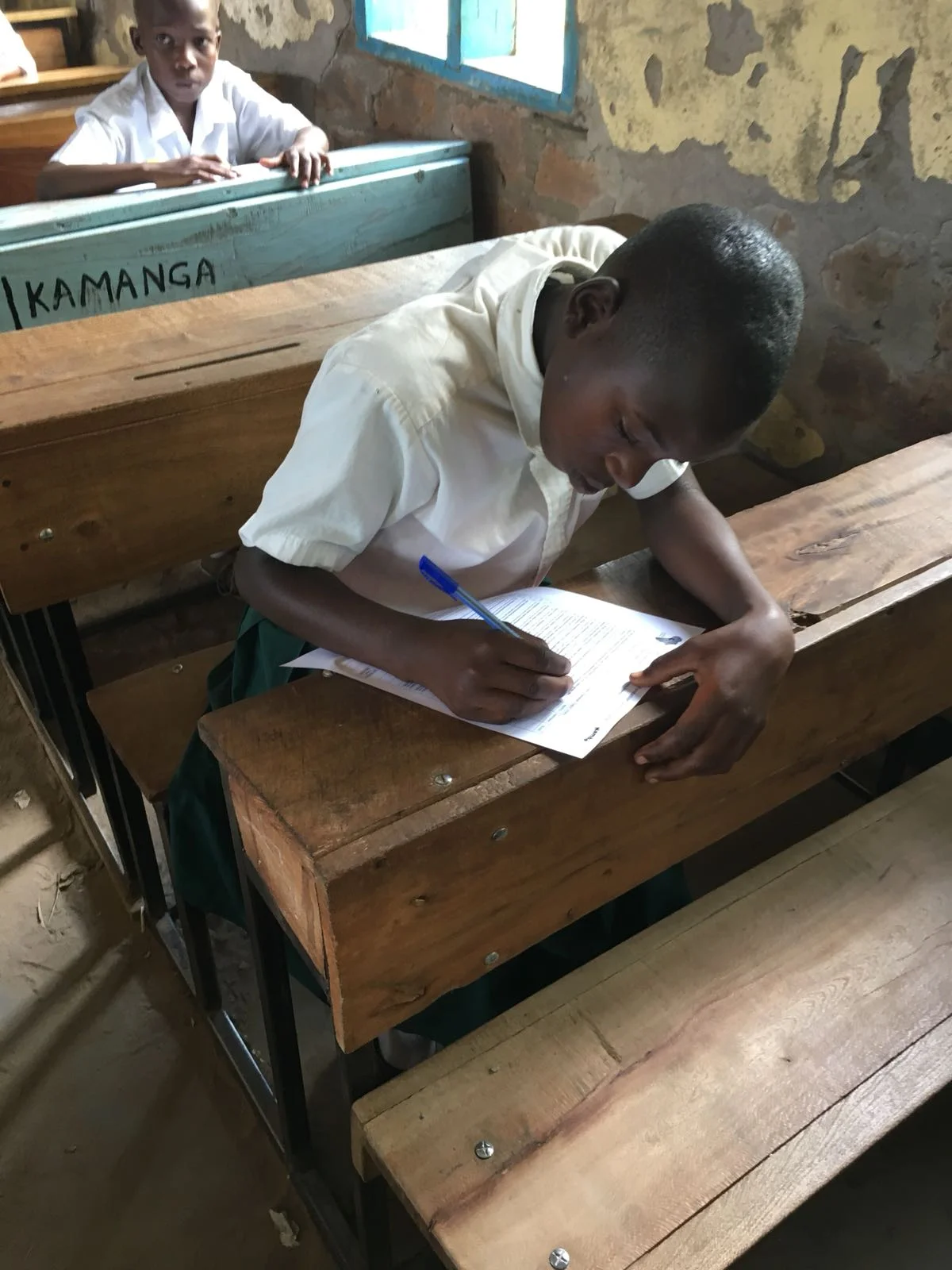

As background information, I was previously teaching biology at a government secondary school in Tanzania for two years. Upon arriving in Kamanga and visiting Nyamatongo Secondary School, it became obvious to me that volunteering some of my time at the school would be beneficial for all parties involved. First and foremost, the school is understaffed, without me volunteering it would be very likely that the first year students would not be taught biology. Secondly, by me spending time at the school I can help to build up relations between Cedar Tanzania and the local education system. It is my hope to identify a few dedicated educators, and start up some type of collaboration with them to improve the quality of education being offered at Nyamatongo Secondary School. By working along side the teachers, I also believe they may see the techniques I use in the classroom, ask me questions, startup dialogs, and possibly implement new methods of teaching into their own lesson plans. Lastly, I have really missed being in the classroom. I am very happy to be back teaching at a school. So really my motivation was threefold, for the school/students, for Cedar Tanzania, and for myself.

What are the challenges of teaching in a local school?

Whether it be a Westerner or a Tanzanian, the first thing everyone thinks or asks about is the language, and yes, the language barrier does create a challenge. Even though I am fluent in Swahili, there are times when it is difficult to find a good translation (especially in biology class). Also, many people don’t realise, but the medium of communication in secondary school in Tanzania is English. This creates a totally different challenge, when do I use Swahili and when do I refrain from using it. The students need to learn English, but if I only use English they will not understand and if I translate into Swahili, the translation might be the only thing students are capable of remembering two weeks later. I have to talk slow, be wise in my word choice, and make sure when new words are introduced all students understand. Outside of language, the biggest challenge is defiantly the class size. My classes currently range between 50-60 students. As with any class, all of the students have different abilities, personalities, and learning styles. This makes it very difficult to keep everyone focused and learning throughout the entire 80-minute double period.

What do you enjoy most about teaching there?

As cliché as it may sound I really enjoy teaching and seeing people learn. Whether I am teaching a student directly or working with a fellow teacher to help them better their craft, I love to see it when that light-bulb goes off in someone’s head, and they do not just know what has been taught to them, but they understand it. For me personally, I love biology and it is very simple, but I know that is only because I had a very good teacher in high school. The challenge of trying to figure out how to teach the students so they can see and understand the simplicity of biology is the other thing I enjoy the most. Biology was not meant to be learnt as facts being presented in a classroom. It was meant to be seen and understood through many simple observations in our daily lives. Trying to put together a lesson plan which will best help the students to understand a topic is very similar to putting together a puzzle.

What is Cedar Tanzania’s future plans in regards to their collaboration with the school?

This question is very difficult to answer at this point in time as I have only been volunteering at the school for a month now. As with any community development work, it is crucial you find the point when your interests and skills intersect with the community’s interests and needs. This is exactly how I became involved with the school in the first place. They had an interest and a need of getting more biology teachers, and I was both trained and interested in teaching biology at the secondary school. As of now it is too soon to know exactly how Cedar Tanzania will collaborate with the school in the future, because many of these variables are still unknown. Currently there are ideas of what could happen in the future. For example, there is already a dormitory under construction at the school, when completed it could reduce some students’ travel time to and from school by as much as 4 hours. Or maybe teachers would like to receive some refresher training on modern teaching techniques with an emphasis on English being taught as a second language within other subject lessons. Again, this will all depend on what the school and its staff need and are interested in pursuing. There are still more discussions that are needed to be had before Cedar Tanzania will know the best way forward in their collaboration with the Nyamatongo Secondary School.